How to write template functions in C++

By now we talked about why we might want to use templates, what happens under the hood when we use them and today we can finally start talking about how to use them.

While there is a lot of intricacies related to templates that often turn the C++ beginners away, I'm going to try to present all (well, ok, most) of the relevant information in the following couple of lectures.

For this one in particular, my ambition is to make it your one-stop shop for all the basics you need to know about writing and using function templates. The class templates I'll leave for the next lecture. So we are starting very gently and will dive deeper as we go.

That being said, I strongly urge you to go and look at the why and the what lectures before if you haven't already. I believe it will make this lecture much easier to digest.

After you're done with those, you should be ready to hear about all the stuff we will cover today:

- The basics of writing a function template

- Explicit template parameters

- Implicit template parameters

- Using both explicit and implicit template parameters at the same time

- Function overloading and templates

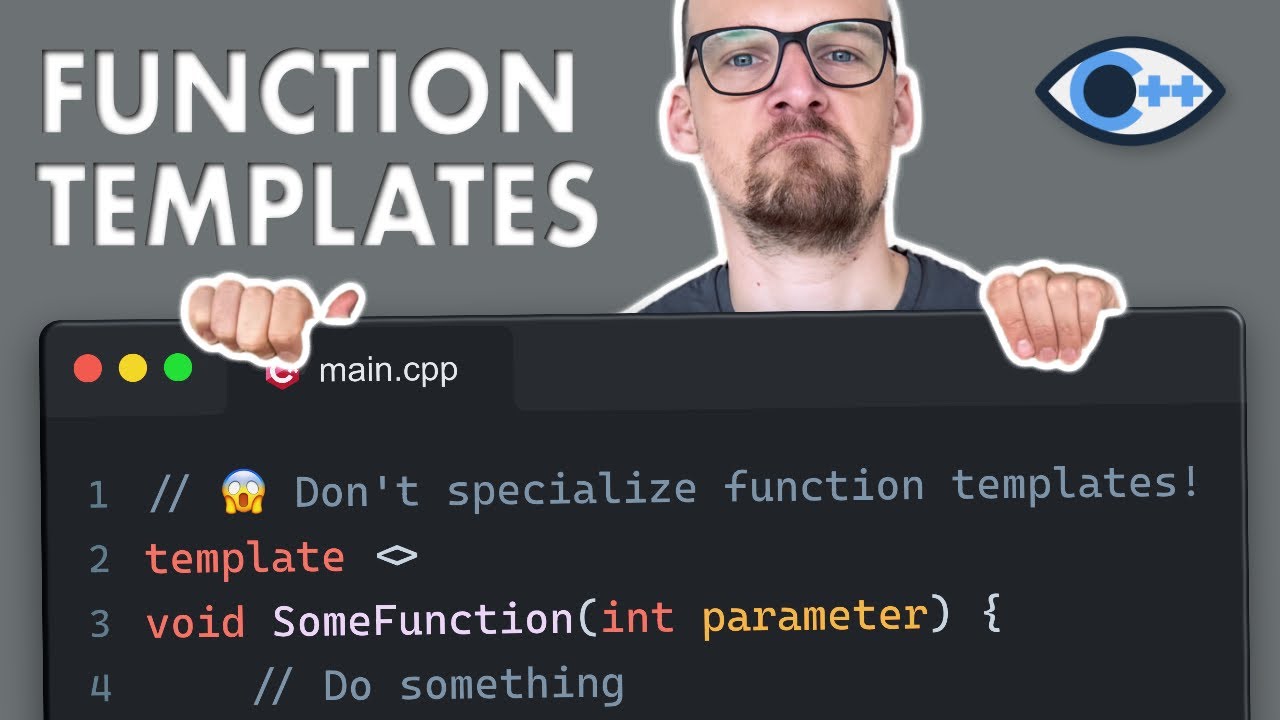

- Full function template specialization and why function overloading is better

- Everything happens at compile-time!

- Summary

Let's start with a very simple function PrintDefaultInteger that just prints a default value of int for now (demo):

#include <iostream>

void PrintDefaultInteger() { std::cout << int{} << std::endl; }

int main() {

PrintDefaultInteger();

return 0;

}Running this tiny program will print a 0 just as we expect. But this feels extremely limiting. If we would want to print a default value of more types we would have to write a lot more of these functions!

Function templates provide us with a better way. To declare a function template we prefix a normal function declaration with the keyword template followed by a list of template parameters.

template <{TemplateParameters...}>

{ReturnType} FunctionName({Arguments...}) {}These template parameters can be used at any place within our function, including its return type, input arguments, or the body of the function. Let us begin with just one of such parameters and rewrite our function PrintDefaultInteger into PrintDefaultValue function template (demo):

#include <iostream>

template <typename T>

void PrintDefaultValue() { std::cout << T{} << std::endl; }

int main() {

PrintDefaultValue<int>(); // T=int

PrintDefaultValue<float>(); // T=float

return 0;

}Straightaway we notice a couple of changes. Now we have a template parameter T that represents any type and we print its default value by calling T{} within a std::cout statement. We could've done many more things with it and can generally treat it as any other type we used before.

We call our function template from main explicitly providing the types int and float for our template parameter at the call site, so the call looks a bit different from how we normally call functions. This is not always the case with function templates but more on that in a couple of minutes.

When the compiler sees our calls it instantiates the specialization of our function template for the requested types and calls the appropriate specialized functions afterwards. If this is confusing, do look into the previous lecture about what templates do under the hood again.

In our simple example here we specify our template parameter with the word typename. Such template parameters are called type template parameters because they represent, well, a type. We could've also used the keyword class instead but I prefer the typename because it indicates that it can stand for any type, while class seems to suggest that it must be, well, a class, or a user-defined type. For whatever reason though this is one of those topics in which there are people with very strong opinions on the matter in either way 😉

The name of the template parameter T, can be chosen arbitrarily but a good rule of thumb is to use a name that is representative of what one wants to do with these types, like Number or Algorithm or whatever this type should represent. Consequently, we will name them just as any other type in PascalCase. That being said you will see T used very often, especially in simpler examples, like the ones in this lecture. Speaking of what these type template parameters represent, they represent, well, types and can be used within our function just like any other type. We could create variables of these types or pass them into further function templates etc.

Now, apart from type template parameters there are more things we can see after the template keyword:

- non-type template parameters

- template template parameters (yes, template word is repeated twice)

- variadic templates

- concepts (from C++20 on)

For now we focus only on the non-type template parameters and we will talk about the rest in the future lectures. Let's illustrate the use of non-type template parameters on a another small example function template PrintValue that receives an int template parameter and prints its value (demo):

#include <iostream>

template <int kNumber>

void PrintValue() { std::cout << kNumber << std::endl; }

int main() {

PrintValue<42>();

PrintValue<23>();

return 0;

}In this example, kNumber is a non-type template parameter. Such template parameters are just compile-time constants of their respective types and when we run the code it will print the values we pass to our template parameters. Before C++20 they could only be integer-like numbers but from C++20 on they can also be floating point numbers or even strings. Oh, and they can also be auto but I wouldn't use auto like this here.

Please note, that the value we provide as our template arguments should be available at compile time, meaning that it either has to be a compile-time constant or a result of a constant expression, so we cannot use a normal non-const variable when instantiating such a function template:

// Somewhere in some function

PrintValue<42>(); // Ok

constexpr int kLocalNumber{42};

PrintValue<kLocalNumber>(); // Ok, value of kLocalNumber is available at compile time

int number{42};

PrintValue<number>(); // ❌ Not ok, won't compile, number is not a constant expressionFor now we've looked at using a single template parameter of each kind. But we can have any number of those in any order. We just have to make sure to provide the explicit template arguments in the same order. Furthermore, the template parameters can have default values. We can specify these default values from the end of the template parameter list although I would recommend not to use default values like these as they can cause quite some confusion once you forget that you set them somewhere deep in your software architecture.

Anyway, as an illustration, for some function template DoSomething we can have a number of template parameters in any arbitrary order and provide the template arguments at the call site in the same order (demo):

template <typename T1, //

int kNumber, //

typename T2, //

bool kCondition, //

typename T3, //

typename T4 = float> // 😱 don't use defaults

void DoSomething() {}

int main() {

// T1=int, kNumber=42, T2=float, kCondition=true, T3=int, T4=int

DoSomething<int, 42, float, true, int, int>();

DoSomething<double, 23, int, false, float, bool>();

// Last template parameter takes default value

DoSomething<float, 42, int, true, double>();

return 0;

}The first call assigns T1=int, kNumber=42, T2=float, kCondition=true, T3=int, T4=int and the last call makes use of the default value of the last template parameter and sets T4=float.

This is more or less everything we have to know about function templates if they don't have any function parameters. If they do have such parameters, that use the template parameters for their types, then the compiler is able to reason about the template parameters based on the types of these provided function arguments. Which is really handy but complicates the things a little. So let's see what it gives us as well as what pitfalls we should be aware of.

We'll start again with a tiny example. With a normal function Print that has a single int parameter:

void Print(int p) { std::cout << p << "\n"; }Nothing magical about this function. We've seen tons of these by now. However, just as before, we want it to be a function template instead because we might want it to work for more than just int arguments.

We can achieve this in exactly the same way as what we've just discussed, by introducing the template keyword before the function as well as specifying all the necessary template parameters using typename or class keywords (of which we will just as before use just typename). We will also again just print the argument of our function (demo):

template <typename T>

void Print(T p) { std::cout << p << std::endl; }We can call this function with any type we want:

int main() {

Print(42); // T = int

Print(42.42); // T = double

return 0;

}And it will work just as we expect and print the output with the correct types int and double:

42

42.42

What is important to note here is that the compiler is able to figure out the template parameter to be int or double purely depending on the function arguments that we provide, without us providing the types explicitly as opposed to what we did before. That being said, we can explicitly provide the type we want. Which makes the following calls equivalent:

int main() {

Print(42); // T = int

Print<int>(42); // T = int

Print(42.42); // T = double

Print<double>(42.42); // T = double

return 0;

}Now, one small remark here, think about what happens if you change Print<double>(42.42) to Print<int>(42.42)?

Now that we are talking about passing arguments to the function, we are still able to do what we learned before and use a constant reference for the input arguments:

#include <iostream>

template <typename T>

void Print(const T& p) { std::cout << p << std::endl; }

int main() {

Print(42); // T = int

Print(42.42); // T = double

return 0;

}Which prints exactly the same things as before.

After we used a const reference with no issue for our template parameter we might become brave and remember stuff that we discussed when we talked about move semantics. So we might want to use a rref && and an input parameter to our function template.

However, the naïve logic fails us here as when we use a type template parameter with && we are not getting an rref, we are getting a forwarding reference (also sometimes called a universal reference):

// 🚨 This is a FORWARDING reference, not an rref!

template <typename T>

void Print(T&& p);These behave slightly differently from normal rrefs and allow to use a single function to handle both normal references and rrefs making use of the std::forward function. We will not go deeper into this here and will talk about it separately.

We can, however, further extend our printing example in a different way, by adding more template parameters into the mix. Just as before, we just extend the template parameter list to more types (demo):

#include <iostream>

template <typename T1, typename T2>

void Print(const T1& p1, T2 p2, T1 p3) {

std::cout << p1 << ", " //

<< p2 << ", " //

<< p3 << std::endl;

}So here, we have two template parameters T1 and T2 that we use to specify the types of our function parameters. And, of course, we can run it by either letting the compiler figure out the template parameters on its own or providing them explicitly:

int main() {

Print(42, 42.42, 23); // T1=int, T2=double

Print<int, double>(42, 42.42, 23); // Equivalent to above

return 0;

}Which results in printing the expected argument values:

42, 42.42, 23

42, 42.42, 23

Actually there is one more thing in this example that we haven't seen before. We have 3 function parameters but only two template parameters. This is to show that there is no need for a 1-to-1 correspondence between their number. This totally makes sense too. Just as we can have a function that accepts 3 integers, we can have a function that accepts 3 different arguments on any same type. In our case, we want the first and the last argument of our function to have the same type (albeit first being a const reference) and only the second argument to be of the different type.

Now, if we fail to match the types of the first and the last argument by, say, providing a double as the last argument as opposed to the expected int:

Print(42, 42.42, 23.23); // ❌ Won't compileWe will cause a compilation issue that says something about "template argument deduction/substitution" failing:

<source>: In function 'int main()':

<source>:12:8: error: no matching function for call to 'Print(int, double, double)'

12 | Print(42, 42.42, 23.23);

| ~~~^~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

<source>:5:6: note: candidate: 'template<class T1, class T2> void Print(const T1&, T2, T1)'

5 | void Print(const T1& p1, T2 p2, T1 p3) {

| ^~~

<source>:5:6: note: template argument deduction/substitution failed:

<source>:12:8: note: deduced conflicting types for parameter 'T1' ('int' and 'double')

12 | Print(42, 42.42, 23.23);

| ~~~^~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Compiler returned: 1You might have already started to wonder - if we have multiple function parameters and multiple template parameters that represent the types, can we provide some types explicitly and let the compiler guess the rest?

And the answer to your question is yes - yes we can! This all gets again slightly more complex but we'll comb through it, no worries! The complications arise because the compiler's ability to guess the types depends partially on the order of the function parameters as well as on the order of the template parameters.

One easy way to think about it is this:

🚨 When we specify the template arguments explicitly, we are specifying them from left to right. Then, when the compiler doesn't see any more explicit template parameters, it looks at the provided function arguments and tries to match them to the function parameters hopefully figuring out the rest of the template parameters in the process:

An example of such a situation could be some function called SomeFunction (yeah, I have no fantasy) that has a number of template parameters as well as function parameters that make use of some of those template parameters (demo):

template<class One, int kTwo, class Three, class Four, class Five>

void SomeFunction(Three three, Four four, Five five, Three one_more) {

// Some implementation;

}

int main() {

// The types guessed in this call:

// One = float

// kTwo = 42

// Three = double

// Four = int

// Five = float

SomeFunction<float, 42>(42.42, 23, 23.23F, 23.42);

}If the compiler fails to figure out the template parameters it will throw an error at us. Just for the sake of example, let's look at a couple of errors that might happen.

If we try to call our function without the last argument:

// ❌ Won't compile.

SomeFunction<float, 42>(42.42, 23, 23.23F);We will get an error along the lines of "candidate expects 4 arguments, 3 provided":

<source>: In function 'int main()':

<source>:13:26: error: no matching function for call to 'SomeFunction<float, 42>(double, int, float)'

13 | SomeFunction<float, 42>(42.42, 23, 23.23F);

| ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~^~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

<source>:2:6: note: candidate: 'template<class One, int kTwo, class Three, class Four, class Five> void SomeFunction(Three, Four, Five, Three)'

2 | void SomeFunction(Three three, Four four, Five five, Three one_more) {

| ^~~~~~~~~~~~

<source>:2:6: note: candidate expects 4 arguments, 3 provided

Compiler returned: 1If we provide a wrong type in the last argument:

// ❌ Won't compile.

SomeFunction<float, 42>(42.42, 23, 23.23F, 42);We will instead get an error about a "conflicting type for a parameter" as the compiler will see that our type Three must be both double and int at the same time to match our template:

<source>: In function 'int main()':

<source>:13:22: error: no matching function for call to 'SomeFunction<float, 42>(double, int, float, int)'

13 | SomeFunction<float, 42>(42.42, 23, 23.23F, 42);

| ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~^~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

<source>:2:6: note: candidate: 'template<class One, int kTwo, class Three, class Four, class Five> void SomeFunction(Three, Four, Five, Three)'

2 | void SomeFunction(Three three, Four four, Five five, Three one_more) {

| ^~~~~~~~~~~~

<source>:2:6: note: template argument deduction/substitution failed:

<source>:13:22: note: deduced conflicting types for parameter 'Three' ('double' and 'int')

13 | SomeFunction<float, 42>(42.42, 23, 23.23F, 42);

| ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~^~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Compiler returned: 1Feel free to experiment with various error messages here to get a feeling for them.

Now I want to switch gears and talk about a very important topic - function overloading. We touched upon it before but now that we have templates in the mix, we have to look at the whole thing again.

Long story short, function overloading allows us to have functions with the same name that differ by their parameters and to look up the correct one to call based on the arguments provided at the call site. This way, should we have two different Print functions, one that takes a double and one that takes an int the compiler will still know what to do:

#include <iostream>

void Print(double number) {

std::cout << "double: " << number << std::endl;

}

void Print(int number) {

std::cout << "int: " << number << std::endl;

}

int main() {

Print(42); // Chooses int

Print(42.42); // Chooses double

return 0;

}It sees the types with which we call our Print functions and picks the correct one - one that takes int when passing 42 and one that takes a double when passing 42.42. So far so good.

The good news is that if we add a function template into the mix, function overloading still works! To show this, let's replace the first of our functions with a function template (demo):

#include <iostream>

template <typename T>

void Print(T number) {

std::cout << "T: " << number << "\n";

}

void Print(int number) {

std::cout << "int: " << number << "\n";

}

int main() {

Print(42); // Still chooses int

Print(42.42); // Chooses template with T=double

return 0;

}If we run this code we will see that the call with 42 as input still chooses the normal Print function that accepts an int, while the call with 42.42 as input now uses our function template. And the main question that you might be having right about now is: "how does a compiler know not to use our function template for 42 too?"

Great question! The reason it prefers a concrete function implementation rather than a template is that the rules of function overloading will always prefer a non-template function to template ones, that is if there is an exact match. Please spend some time experimenting with this. Write various functions, see how the compiler always uses a matching concrete implementation rather than a template.

But the overloading story does not end there! We can do so much more with overloading! Just like with any normal type, we can treat our template parameter as just such normal types and largely speaking, if we forget about the template prefix along with its template parameters, then the template functions can be overloaded just as any other function can.

Let's see a concrete example, where we will overload our function template Print for a case when it accepts pointers and for a case when it accepts a vector of elements (demo):

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

template <typename T>

void Print(T number) {

std::cout << number << std::endl;

}

template <typename T>

void Print(T* ptr) {

std::cout << "pointer: " << *ptr << std::endl;

}

template <typename T>

void Print(const std::vector<T>& vec) {

std::cout << "vector: ";

for (const auto& element : vec) {

std::cout << element << " ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

}

int main() {

Print(42);

int number{23};

Print(&number);

Print(std::vector{1, 2, 3});

return 0;

}And if we run it we will get the output that shows that the compiler is able to pick the correct overload when we pass a pointer or a vector into our Print function:

42

pointer: 23

vector: 1 2 3

The intuition behind it (which can actually go quite a long way) is that the compiler will pick that overload which is more specific to the input. So when we pass a vector it actually fits to two of our Print functions, as it also fits into the basic implementation. However, the vector overload is much more specific - it only accepts vectors, while the basic function accepts vectors and all other sorts of types. So the compiler considers the vector overload to be more specific and picks it. The same story holds for the pointer.

Now, try to answer yourself, what if we add our Print(int) function back into the mix? What will change?

Just as we could overload on a pointer type just now, we technically can overload on reference types. The problem is that while a pointer has its own semantics and the compiler is happy to distinguish it from a normal variable, this is not the case for the references.

This results in us not being able to have both the version that accepts T and the version that accepts a reference type, say const T& (demo):

template <typename T>

void Function(T parameter);

template <typename T>

void Function(const T& parameter);

int main() {

Function(42); // ❌ Won't compile

}If we try to compile the above we're going to get a compilation error along the lines of the call being ambiguous:

<source>: In function 'int main()':

<source>:8:11: error: call of overloaded 'Function(int)' is ambiguous

8 | Function(42); // ❌ Won't compile

| ~~~~~~~~^~~~

<source>:2:6: note: candidate: 'void Function(T) [with T = int]'

2 | void Function(T parameter);

| ^~~~~~~~

<source>:5:6: note: candidate: 'void Function(const T&) [with T = int]'

5 | void Function(const T& parameter);

| ^~~~~~~~

Compiler returned: 1The reason for this is that there is no way for the compiler to figure out at the call site which version we mean. So we can't use both overloads at the same time. However, in most cases we should be good with using constant references by default. If we need to squeeze more performance by copying small types we will have to go towards partial specialization with classes instead. And for those cases when we need to forward ownership of an object through a function we have the forwarding reference that I mentioned before.

Now one last thing to talk about today is template specialization. Generally speaking it can be of two kinds: full and partial. However, function templates can only be fully specialized so we will only talk about that kind today.

The funny thing is that this kind of specialization basically serves exactly the same purpose as function overloading. And considering that we have this very powerful overloading mechanism for functions that works mostly as we expect it to, the experts in C++ like Herb Sutter and by extension CppCoreGuidelines suggest that we should not specialize function templates at all 🚨.

That being said, it is not uncommon to find code that does specialize a function template. To deal with this code we must still know how specialization looks like and more or less how it is supposed to work. So that's what we'll focus on in the remainder of this lecture.

Let us for this go back to the example from before where we had a function Print that was accepting any argument:

#include <iostream>

template <typename T>

void Print(T number) {

std::cout << number << std::endl;

}

int main() {

Print(42); // T=int

Print(42.42); // T=double

return 0;

}Now let's say that we want this function to do something different for some random type, for simplicity let's pick int. We already know that we could overload this function and just write a normal function that accepts an int but we could also specialize our function instead. In order to specialize a function template, we write template <> before the chosen template specialization and then use the types we wanted to in the first place when writing the rest of our function (demo):

#include <iostream>

template <typename T>

void Print(T number) {

std::cout << number << std::endl;

}

// 😱 Not a great idea, overloading is better!

template <>

void Print(int number) {

std::cout << "int: " << number << std::endl;

}

int main() {

Print(42); // Picks specialization

Print(42.42); // Picks base function template

return 0;

}Here, we provide such a specialization for our Print function and this will do the trick. If we pass 42 as an argument into the Print function the compiler will pick the specialization, while for any other type of argument it will use the base function template.

So if all seems to be working then what't the issue? Why is it that it is suggested to not specialize function templates?

This topic is quite confusing because of the complicated rules of template argument deduction. The best thing I can do is give a couple of examples that look a little counterintuitive to me (and to many other people for that matter).

Let us start with an example related to passing objects by const references. Assuming we have some relatively large object Object we would have the code that does something with it using a function template Process. Now we want some special processing for our Object so we have a bright idea to specialize the function template Process and we use a const Object& as an input type because we don't want to copy our object (demo):

#include <iostream>

struct Object {

Object() = default;

Object(const Object& other) { std::cout << "copy\n"; }

// 😱 Omitting the rule of all or nothing for shortness.

};

template <typename T>

void Process(T object) {

std::cout << "base\n";

}

// 😱 Not a great idea, overloading is better!

template <>

void Process(const Object& object) {

std::cout << "specialization\n";

}

int main() {

const Object object;

Process(object);

return 0;

}Intuitively, looking at the code one could expect that a specialization that fits perfectly to accept our const Object& would be called, but unfortunately if we run this code, we get the following output:

copy

base

This indicates to us that the specialization was not called and the object was copied because the Process base function template was called instead.

The reasons for this are slightly involved but the idea is this: template argument deduction never deduces a reference type, so T cannot be a reference type. In our case it deduces T=Object, which means that there is a function instantiated from our template void Process<Object>(Object) which is the exact match to the object that is being passed. This instantiation is better than our hand-written specialization that takes a reference type instead. So the compiler never picks our specialization. At least that's my understanding for now.

We can fix it in a hacky way, by explicitly forcing the compiler to pick the right specialization by changing the call to our function:

-Process(object);

+Process<const Object&>(object);With this modification, the correct specialization is called and the object is not copied. But it is quite hacky and still the actual better solution would be to overload the function instead of specializing it:

#include <iostream>

struct Object {

Object() = default;

Object(const Object& other) { std::cout << "copy\n"; }

// 😱 Omitting the rule of all or nothing for shortness.

};

template <typename T>

void Process(T number) {

std::cout << "base\n";

}

void Process(const Object& number) {

std::cout << "overload\n";

}

int main() {

const Object object;

Process(object);

return 0;

}If we run this example we get the expected output:

overload

So the object is not copied and our overload is preferred to the general function template.

Another classical example is the so-called Dimov/Abrahams example. It involves both a function template overload and a function template specialization and has confused a lot of people in its time. Here is how it goes. We have a function template Process and its specialization for int* parameter. We then create an int* variable and pass it as a parameter to a function Process:

#include <iostream>

template <class T>

void Process(T) { std::cout << "base\n"; }

template <>

void Process<>(int*) { std::cout << "specialization\n"; }

int main() {

int* pointer{};

Process(pointer); // Calls the specialization.

}The compiler sees that there is a template, sees a specialization too and correctly picks it. So we're all good for now.

The confusing parts begin if we now add an overload for any pointer type after the specialization (and it is important that it happens after):

#include <iostream>

template <class T>

void Process(T) { std::cout << "base\n"; }

template <>

void Process<>(int*) { std::cout << "specialization\n"; }

template <class T>

void Process(T*) { std::cout << "base overload\n"; }

int main() {

int* pointer{};

Process(pointer); // Now the overload is called instead! 🤯

}If we run this code the overload is going to be called, not the specialization!

This is confusing because our specialization is still the exact match to the type we pass! So if it happens that we have an overload after we defined a perfect specialization that fits to our passed argument exactly, suddenly this overload will be picked?

Now, the key to understanding this behavior is really well described by Herb Sutter in his post Why Not Specialize Function Templates and goes as follows. The specializations do not participate in overload resolution! Which means that first an overload is picked, and only then a specialization of that selected overload is picked, if any. So, in our case, the Process(T*) is a better overload so it is selected. The Process(int*) specialization is not selected as it is a specialization of Process(T) and not the Process(T*). Anyway, just making it an overload fixes the issue for good:

#include <iostream>

template <class T>

void Process(T) { std::cout << "base\n"; }

void Process(int*) { std::cout << "overload\n"; }

template <class T>

void Process(T*) { std::cout << "base overload\n"; }

int main() {

int* pointer{};

Process(pointer); // Selects the correct overload.

}By the way, if you made it this far, I have a question for you. What will happen if we move the specialization below the overload in the original example?

#include <iostream>

template <class T>

void Process(T) { std::cout << "base\n"; }

template <class T>

void Process(T*) { std::cout << "base overload\n"; }

template <>

void Process<>(int*) { std::cout << "specialization\n"; }

int main() {

int* pointer{};

Process(pointer); // What's called here?

}Write your answers in the comments to the video including the reasoning for what is happening and let's chat about it there!

One final thing for today is that everything related to templates happens at compile time. Which has its consequences. One of the errors that I see beginners do (and did it myself some many years ago) is to assume that the compiler cares about the logic inside of the function when it compiles it. The reasoning goes along the way that if we logically guarantee that a code path will never be taken then it's ok for this path to not compile and the compiler should still be fine with this. Unfortunately, this is not the case.

Let us illustrate this with an example. Let's say we have a function GetLength that should return lengths of various objects. And it has a couple of template parameters, the non-type enum value representing which type we expect and then the type template parameter that actually represents the type of the function parameter. We then try to write the code that logically seems quite sane:

#include <string>

enum class Type {

kString, kNumber

};

template <Type kType, class T>

std::size_t GetLength(const T& param) {

if (kType == Type::kString) {

return param.size();

}

return 1;

}

int main() {

std::string s{};

GetLength<Type::kString>(s);

GetLength<Type::kNumber>(42);

}We have an if statement in our function and we pass the Type::kString enum value whenever we use our GetLength function with string and the Type::kNumber value when we use it with a number. It might be reasonable to assume that this code should compile but it does not with an error that complains on our number not having the size() method:

<source>: In instantiation of 'std::size_t GetLength(const T&) [with Type kType = Type::kNumber; T = int; std::size_t = long unsigned int]':

<source>:18:29: required from here

<source>:10:22: error: request for member 'size' in 'param', which is of non-class type 'const int'

10 | return param.size();

| ~~~~~~^~~~

Compiler returned: 1The reason for this is actually quite simple. The compiler does not care about the logic in our function as that logic is runtime logic. It cannot assume that just because we did not happen to call all the possible paths through our function nobody else would. In the end, if this function gets compiled into a library and distributed, somebody might call it in a different way, so it has to compile as a whole. And of course it doesn't, because many types don't have the size() method.

I've seen this mistake being made countless times so I wanted to explicitly mention it here.

I also have a piece of good news related to this. We now live in the world of modern C++, that is at least C++17, and we have more tools at our disposal to achieve what we want in this situation. What we could do now is to use the if constexpr - a compile-time cousin of the normal runtime if, which will allow the compiler to actually conditionally compile parts of our function based on the provided parameters (demo):

#include <string>

enum class Type {

kString, kNumber

};

template <Type kType, class T>

std::size_t GetLength(const T& param) {

if constexpr(kType == Type::kString) {

return param.size();

}

return 1;

}

int main() {

std::string s{};

GetLength<Type::kString>(s);

GetLength<Type::kNumber>(42);

}With this change the code compiles and runs as expected. If we're feeling adventurous we could even say that with this example we dipped our feet into compile-time meta programming. 🤘 In reality we don't really need an explicit enum for purposes similar to the one in the example and we have more tools for conditional compilation as well as tools for estimating traits about our types but more on that in the future.

If you've made it this far, you are a hero! You're clearly interested in templates and determined enough to listen to me ramble about them for a long time.

I know this seems like it is a lot of information at once, but trust me it becomes easier with time. Also, we covered not only the basics of using function templates but also what not to do as well as why we shouldn't do it. Which doesn't help making this lecture easy to digest but will make your life easier going forward.

Anyway, as a very short summary, today we covered most of the important parts of function templates. We know how to define them, what template parameters they can accept and how to call these function templates. Furthermore we now know that we can and should overload function templates but we probably should steer away from specializing them.

And honestly, with this information at our disposal, we can go a pretty long way in the world of generic programming.

The next lecture is going to still focus on how to use templates, but now for classes, where there are slightly more details and where specialization actually does play a much more important role than with functions. But if this lecture is firmly placed within our heads we should have little issues figuring out class templates too.