-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 2

Home

staej : A Graphical Tool for Parsing and Inspecting the JIGSAWS Dataset This page contains the updated version of the original companion document for the application.

This document is about the application set called staej [steɪd͡ʒ].

It contains the description of the JIGSAWS project, a summary of the development history, a user and developer manual for the application and finally a discussion of possible future applications and improvement.

The application consists of two components. An easy-to-use command line tool for importing the files once and the visual interface for working with the imported data. The former is the enter-staej.py utility, the latter is the staej viewer.

Both are written in Python 3 and primarily tested under Arch Linux. The GUI uses the GTK 3 toolkit (via PyGObject). The dataset is stored locally in SQLite but it’s technically easy to adapt it later for other databases like MySQL, Oracle Database or Microsoft SQL. The JIGSAWS video files are stored uncompressed in the filesystem under the user’s config directory (ie ~/.config/staej on Linux and %APPDATA%\staej on Windows).

The Project is available on GitHub under the MIT license.[1]

This paper is about JIGSAWS, a dataset acquired from monitoring three surgical training exercises, that were performed by eight surgeons through multiple iterations. The video and kinematic data was captured using the da Vinci Surgical System (dVSS) using its regular stereo endoscope camera and research interface. This was then extended using a combination of manual annotation and programmatic models. This set was compiled as a collaboration between Johns Hopkins University and Intuitive Surgical Inc (creators of the da Vinci) as part of the larger Language of Surgery project that aims to apply the techniques used for human language analysis to the surgical field.

The stated goal of this project was to study dextrous human motion. This can help us to understand and support the process of skill acquisition, it can aid in developing to better, more objective skill assessing technologies, and to better automation in the field of human-machine collaboration. This type of knowledge can help if the field of surgery by aiding the surgeons in acquiring technical skill, thus reducing the chance of complications.

A follow-up study by some of the same authors reported on several automated segmentation and annotation techniques used on JIGSAWS. [3]

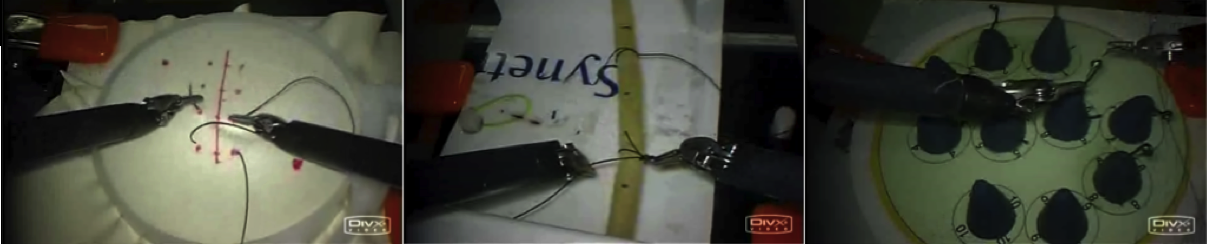

Throughout exercises the camera was not moved and it was not permitted to use the clutch. Three surgical tasks were recorded:

- Suturing: the subject closes a simulated incision by passing the needle through the material at predetermined points

- Knot-Tying: the subject ties single-tie knot on suture attached to a flexible tube

- Needle-Passing: the subject passes the needle through small metal hoop

Figure 1. The three surgical tasks in the order they are mentioned above.

There were 8 subjects marked with the letters B - I. Their respective experience and skill levels are annotated in the meta file. Each subject repeated every task 5 times, these are called trials. A specific trial is uniquely identified by what the paper calls “TaskUidRep”[1] that follows the {task}_{subject}00{trial} format, for example Knot_Tying_B001.

Within staej “TaskUidRep” is simply called file_name, because it’s the video file’s name without the channel “channel1” / ”channel2” suffix and the extension.

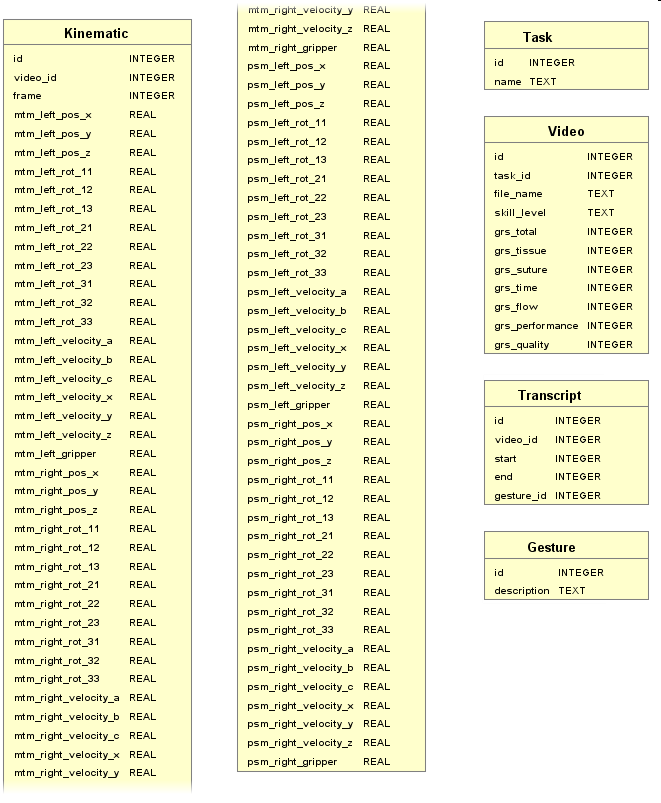

The kinematic data was captured using the dVSS API at 30Hz, same as the video and they are synchronised, so there is a clear mapping between the video and the kinematics at any point in time. Each record contains four sets of measurements for the two arms on the master side console (left and right master tool manipulators) and the first two patient-side manipulators on the robot. Each set contains:

- 3 variables: tool tip position (x;y;z)

- 9 variables: tool tip rotation matrix (R)

- 3 variables: tool tip linear velocity (x’; y’; z’)

- 3 variables: tool tip rotational velocity (α’; β’; γ’)

- 1 variable: gripper angle velocity (θ)

This is also the order of columns within staej’s Kinematics table.

Each of the trials were manually annotated by identifying spans of time when specific atomic units of the surgical activity (“gestures”) were performed. The dataset contains a vocabulary of 15 different gestures. The gestures were designated and identified with the assistance of experienced surgeons. Apart from some empty space in the beginning and end of some videos, each frame was assigned.

The performance of each trial was also annotated by an experienced gynecologic surgeon using a modified OSATS [3] approach that excluded non-applicable items.

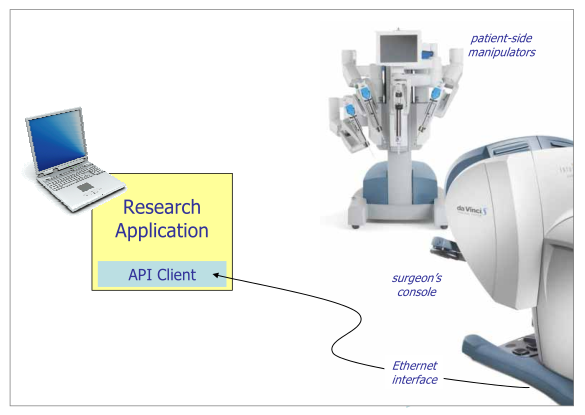

The research interface allows third party developers to monitor the dVSS in real time through a TCP/IP infrastructure. This gives access to the kinematic data as well as user events in real time with the purpose to aid third party developers and researchers in working with the da Vinci. The API server is situated inside the da Vinci System and it’s accessible through standard Ethernet connection.

The kinematic information is sampled at a custom rate specified by the client (between 10 and 100 Hz) and it streams data from the Endoscope Control Manipulator (ECM), the MTMs and the PSMs.

Additionally, the interface transmits asynchronous information, including when the head sensor is triggered, the clutch is pressed or released or when the manipulator arms are swapped. In the JIGSAWS project these were relevant in ensuring the controlled scenario outlined in the previous chapter.

Figure 2. The da Vinci Research interface, also known as the da Vinci Surgical System API

Python is an interpreted, object-oriented, high-level programming language with dynamic semantics created by Guido van Rossum. It has a lot of built-in features and a very convenient package manager called PyPI. It’s free and open source with support for most platforms. It has libraries and bindings for many tasks in the world of science and engineering. I chose this language because of practical reasons, as it is already widely used in robotics for other tasks such as image recognition.

SQLite is a transactional database engine that is compliant with the SQL standard. As such it has drop-in support with many SQL client libraries, including Peeweee. SQLite has a unique property as it is designed for small scale, self-contained, serverless, zero-configuration applications. Instead of the usual client-server architecture, the entire database is stored as a single file on the hard disk. [7] This is advantageous for the purpose of staej as it makes setup uncomplicated and it can be done purely on userland without administrator intervention. Additionally the command line tool can export the data into SQL file[8], opening the window for simple migration to other SQL-compliant databases (such as MySQL) should the need and opportunity arise.

Peewee was my python ORM of choice. It has built in support for SQLite, MySQL and Postgresql support but it works well with any other Python database driver that’s compliant with the DB-API 2.0 specification. [9] I’ve taken a code-first approach to make the project even less reliant on the specificities of the choice of SQL engine.

ORM: object-relational mapping tool. A software library that acts as the compatibility layer between the application and the relational database enabling the developer to treat database entities as objects

GObject is the fundamental generic type system at the heart of GLib-based applications (including GTK applications). It’s a C-based object oriented system that is intentionally easy to map onto other languages. It’s distinguishing aspect is its signal system and powerful notification mechanism. [10] It is used by staej indirectly through GTK and GStreamer but also directly through its enhanced MVVM style base class GNotifier.

GTK+ is the widget toolkit used in staej. It was chosen mainly because of its wide platform support and because it’s part of the GLib ecosystem so it can harness all of the power of GObject as well as other libraries like GStreamer.

GStreamer is a pipeline based streaming framework with a modular system and many plug-ins. It is written in C and its elements inherit from GObject. While it’s designed for audio and video it can stream any data[11], although staej only uses it for DivX video. In its current state this project could have used many other video player libraries, but the advantage of GStreamer becomes apparent near the end of this document in chapter 6.1 Future Development. Adding features that require realtime video manipulation is much easier when we have access to the components of the pipeline as in GStreamer.

The previous three are all C libraries, however they are all accessible from Python thanks to the dynamic bindings in the PyGObject library.

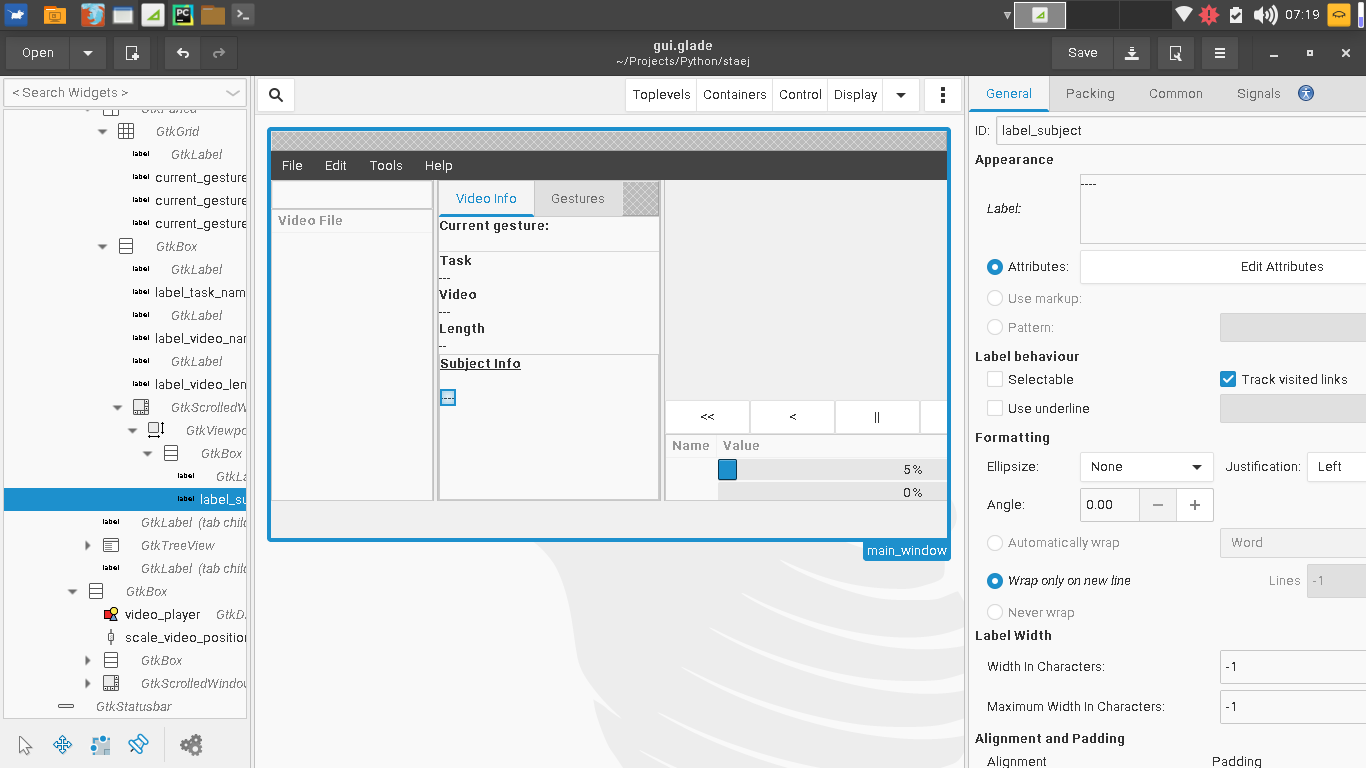

Glade is a graphical user interface designer that creates XML files in the GtkBuilder format. It provides a language-independent, declarative way to design the user interface and attach events. The Gtk.Builder class is used to import the UI file into GTK+.

This is the script used to create the SQLite database from the ZIP files in the JIGSAWS distribution. It creates the required directory structure (enter-staej.py) and then parses the texts in the archives and extracts the videos into the config directory based on that data (import_zip.py).

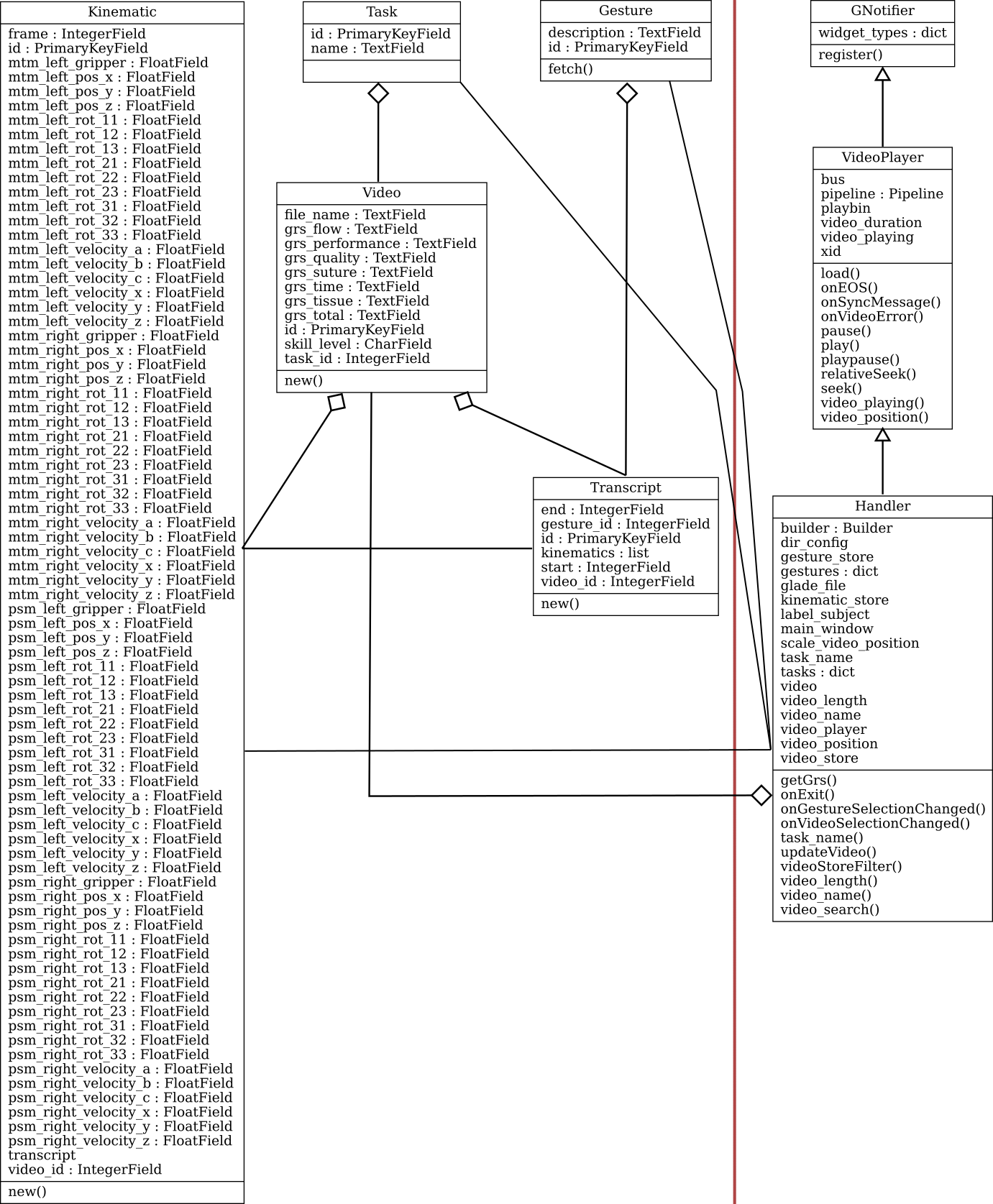

The CSV parsing logic for the text files is located in the model.database package in the ORM objects used by peewee. Their object structure is equivalent to the database structure seen on the next page.

The main application relies on enter-staej.py to have the database ready. It will display an error message with instructions how to use enter-staej.py in that case.

Figure 3 The database as generated by enter-staej.py (Kinematic table broken in half to fit page constraints)

The main application is a visual front-end, so I paid specific attention to the user interface design. The Glade Interface Designer was instrumental in creating the view portion of the application.

Figure 4. Glade with the gui.glade file opened

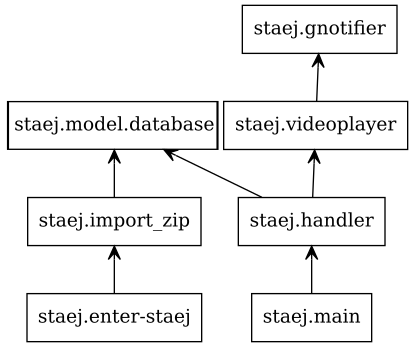

Figure 5. Package Structure

Some of the classes are part of the database model (on the left). There are controller classes too (on the right), that form an inheritance chain with different levels of tasks.

Figure 6. Class Structure

This class has the lowest level of responsibilities. It acts as an event registrar with the purpose to approximate a ViewModel of the MVVM architectural pattern. It inherits from GObject.Object so it emits the notify event when one of its properties is changed.

When the register(self, name, handler_or_widget, default_value = None, set_converter = None, get_converter = None) method is called the instance binds a property (by name) to a widget and guarantees automatic “one way from source” or “two way” updates between the property and the widget. By default it supports widgets that descend from

- Gtk.Label (one way binding)

- Gtk.Entry

- Gtk.Range (eg. Gtk.HScale)

However it can be extended with the widget_types dictionary field. It expects a type as its key and an (update, signal_name, signal_handler) tuple as its value.

It’s possible to convert the parameter between types, set_converter is used to change the value that goes out to the widget while get_converter is used to parse back the widget’s value into a type or format expected by the property. Both take one parameter and return the converted result.

VideoPlayer encapsulates the GStreamer features and the technical interactions between GStreamer and GTK+. It provides error handling and a number of commonly useful properties (video_playing, video_duration, video_position) and methods (playpause, play, pause, seek, relativeSeek) for convenience.

Handler contains all of the high level features related to the specific implementation of staej. It also registers the bindings and and handlers provided by its ancestor classes.

Python 3 and Peewee must be installed as a dependency to both components and the JIGSAWS zip files must be downloaded to disk. Python 3 can be acquired from https://www.python.org/downloads/ while Peewee can be installed via python’s package management system, pip (pip3 on some systems):

$ pip install peeweeAs a command line application enter-staej only does one thing: prepares the environment for staej. Its usage can be learned learned from the help screen accessed with the usual -h or --help argument:

$ python3 enter-staej.py --help

usage: enter-staej.py [-h] [--db] [zipfile [zipfile ...]]

STAEJ command line interface

positional arguments:

zipfile path of the JIGSAWS zip file

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--db create or recreate the working SQLite database

In practice the user will use one of the following three examples below:

-

python enter-staej.py jigsaws/*.zipThe simplest way to initialize all of the exercises into the database. -

python enter-staej.py --db jigsaws/*.zipThis will force to re-create the database and overwrite any file created earlier. -

python enter-staej.py jigsaws/Suturing.zipWhen you have additional archives, they are simply added to the database while preserving the existing content.

Additionally if a portable distribution is needed, the APPDATA environment can be set to the project directory where enter-staej.py and main.py are. In Linux this can be done like below:

$ cd staej

$ export APPDATA=$(pwd)Staej depends on the initialization by enter-staej so its requirements apply here as well. Additionally the following dependencies are required:

-

PyGObject: best to get it through the operating system’s package manager

On Windows MSYS2 [12] must be used:

pacman -S python3 mingw-w64-i686-gtk3 mingw-w64-i686-python3-gobject mingw-w64-x86_64-pygobject-devel -

GStreamer: depending on the operating system this may already be installed, otherwise the system’s package manager should be used. For Windows/MSYS2 the following command can be applied:

pacman -S mingw-w64-i686-gst-python mingw-w64-i686-gst-plugins-good mingw-w64-i686-gst-plugins-bad mingw-w64-i686-gst-plugins-ugly mingw-w64-i686-gst-plugins-base mingw-w64-i686-gst-libav

The application is started with the following command:

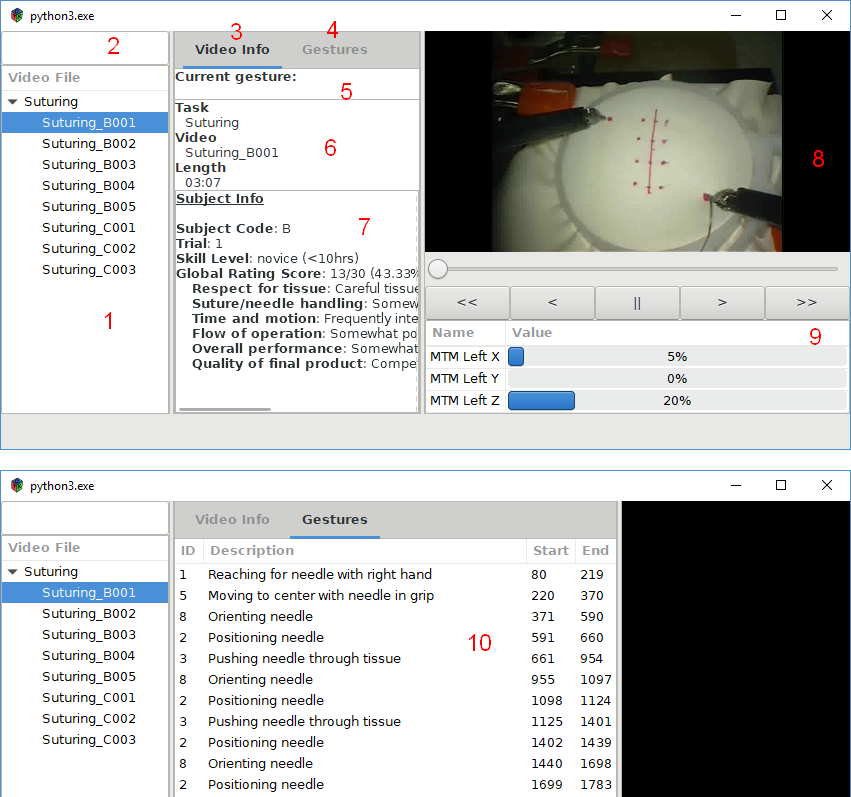

$ python3 main.pyOnce the window appears the user can select a trial from the tree on the left side, where they are grouped by tasks. Once a video is selected, the rest of the window gets updated:

Figure 7 . The main screen of staej and the second tab

- The video file selector where the available trials are listed

- The search bar used to filter by video name

- The Video Info tab shows a selection of general information about the trial as can be seen on the top half of the picture.

- The Gestures tab can be selected by clicking there.

- Shows the gesture at the video’s current timestamp.

- Some generic information about the video.

- Information about the subject (surgeon) and their ratings on this video.

- The video is played here and can be controlled with the user interface below.

- The play/pause (||) button is used to enable or disable playback.

- The slow forward/backward (<, >) buttons skip one frame (1/30 s) and also pause the playback.

- The fast forward/backward (<<, >>) buttons skip a whole second but have no effect on whether the video is playing or paused.

- The kinematics box shows the current state of all kinematic variables at the moment of the currently displayed frame.

- The Gestures panel is a “playlist” style interface where the user can jump to the beginning of a specific gesture within the video. The start and end

Of course every software can be further expanded and polished and staej is no exception. Below are a couple ideas which I’m considering to add at a later date.

- Stereoscopic viewing Right now only the left channel is used of the stereo endoscope capture. The option to enable anaglyph 3D or full screen side-by-side video could improve the user experience. (perhaps even streamed to an external device using Google Cardboard or similar technology) However it has not been tried in this version. I had doubts if it is possible considering that some of the videos have different white balance between the channels so the stereo footage might be sub-par or even painful to watch.

- Gesture explorer A separate window to compare the annotations of the same exercise and compare the kinematics of the same gesture in different trials. After some kind of normalization this could be a helpful tool to detect more nuanced differences between the smaller dextrous movements of surgeons with different skill or experience levels.

- Exporting to CSV, JSON or MatLab M file It’s relatively easy to export data with queries using a database client. But if the gesture explorer is implemented then exporting those processed datasets as well as parts of the original kinematics or annotations will be an attractive feature.

- CGI visualization The kinematics in the dataset contain all the information required to animate 3D models of manipulators on both the master console and the patient-side robot. First, appropriate models have to be sourced or created. Once they are available this will enable the application to visualise the MTMs for which there is no video footage. It also opens the possibility to view the PSMs from a different angle. To enhance the latter experience the video could be projected onto the scene as texture.

- Optimised enter-staej.py performance Ideally the importing phase is only used once on each computer. Even though it can take a very long time, it was deemed a low priority because of that.

- Charts It should be possible to display some of the kinematic data as series in line charts to give a better picture about their change over time. This was planned for the current version but omitted due to time limitations as I wasn’t able to properly dive in into cairo before the deadline.

- Video sorting and grouping Perhaps we want to group the trials by subject or index or to sort them by length, GRS score (total or component). We could also filter by these properties or by the constituent gestures.

I have described staej, a toolset comprised of two applications that respectively import and visualize data from the JHU-ISI Gesture and Skill Assessment Working Set. It is released as an open source project available on GitHub [4].

- David El-Saig, staej git repository (https://github.com/DAud-IcI/staej) [Accessed: 2018-05-01]

- Yixin Gao, S. Swaroop Vedula, Carol E. Reiley, Narges Ahmidi, Balakrishnan Varadarajan, Henry C. Lin, Lingling Tao, Luca Zappella, Benjamín Béjar, David D. Yuh, Chi Chiung Grace Chen, René Vidal, Sanjeev Khudanpur and Gregory D. Hager: The JHU-ISI Gesture and Skill Assessment Working Set (JIGSAWS) - A Surgical Activity Dataset for Human Motion Modeling, MICCAI Workshop, 2014.

- J. Martin, G. Regehr, R. Reznick, H. MacRae, J. Murnaghan, C. Hutchison, and M. Brown. Objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSATS) for surgical residents. British Journal of Surgery, 84:273–278, 1997.

- Narges Ahmidi, Lingling Tao, Shahin Sefati, Yixin Gao, Colin Lea, Benjamın Bejar Haro, Luca Zappella, Sanjeev Khudanpur, Rene Vidal, Fellow, IEEE, Gregory D. Hager, A Dataset and Benchmarks for Segmentation and Recognition of Gestures in Robotic Surgery, Transaction of Biomedical Engineering, 2017.

- Simon P. DiMaio and Christopher J. Hasser: The da Vinci Research Interface, MIDAS Journal, 2008. (reference URL as requested on website: http://hdl.handle.net/10380/1464)

- Python Software Foundation, https://www.python.org/ [Accessed: 2018-05-06]

- About SQlite, https://www.sqlite.org/about.html [Accessed: 2018-05-06]

- Command Line Shell For SQLite, https://www.sqlite.org/cli.html [Accessed: 2018-05-06]

- Adding a new Database Driver, http://docs.peewee-orm.com/en/latest/peewee/database.html#adding-a-new-database-driver [Accessed: 2018-05-06]

- Introduction: GObject Reference Manual, https://developer.gnome.org/gobject/stable/pr01.html [Accessed: 2018-05-06]

- Wim Taymans, Steve Baker, Andy Wingo, Ronald S. Bultje, Stefan Kost: GStreamer Application Development Manual (1.10.1), GStreamer Team, 2016

- MSYS2 installer, http://www.msys2.org/ [Accessed: 2018-05-07]

- Creative Commons: Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ [Accessed: 2018-05-08]

When not otherwise noted below, the pictures are created by me and are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 License. [13]

-

Figure 1 Yixin Gao, S. Swaroop Vedula, Carol E. Reiley, Narges Ahmidi, Balakrishnan Varadarajan, Henry C. Lin, Lingling Tao, Luca Zappella, Benjamín Béjar, David D. Yuh, Chi Chiung Grace Chen, René Vidal, Sanjeev Khudanpur and Gregory D. Hager: The JHU-ISI Gesture and Skill Assessment Working Set (JIGSAWS) - A Surgical Activity Dataset for Human Motion Modeling, MICCAI Workshop, 2014., Page 3 Figure 1

-

Figure 2 Simon P. DiMaio and Christopher J. Hasser: The da Vinci Research Interface, MIDAS Journal, 200.8, Page 2 Figure 1